Monday’s resignation of Joseph Ratzinger—Pope Benedict XVI—as head of the Catholic Church provoked statements of surprise and concern within ruling circles internationally.

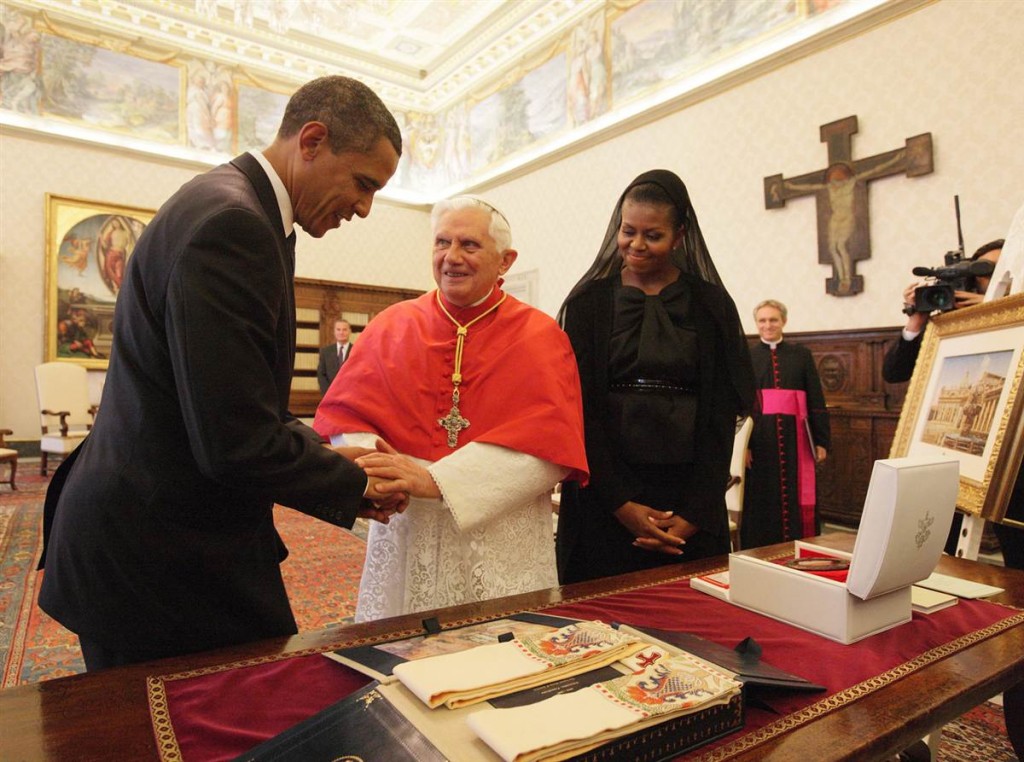

These sentiments expressed by US President Barack Obama, British Prime Minister David Cameron, German Chancellor Angela Merkel, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and many others were not motivated fundamentally by any preoccupation with the personal fate of the 85-year-old Ratzinger.

Rather, what worries governments and financial elites is that the resignation is another indication of deep-going crisis within the Roman Catholic Church, one of the most critical bastions of social and political reaction worldwide.

A resignation by a sitting pope is unprecedented in the modern era. The last individual to voluntarily abdicate was Pope Celestine V, who quit after five months in 1294, declaring himself incompetent for the job. With the few exceptions of those forced out, every other pope has remained as head of the Church until death.

Ratzinger stated Monday that his deteriorating health had created an “incapacity to adequately fulfill the ministry entrusted to me.”

On Tuesday, however, the Vatican spokesman clarified that “Pope Benedict XVI’s decision to resign is not due to ill health but the inevitable frailty that comes with aging.” He added, “His general health was normal for a man nearing 86 years of age.”

Speaking to reporters in Germany, the pope’s brother, George Ratzinger, also said that his brother was “relatively well.” He pointed to concerns other than health.

“Within the church a lot of things happened, which brought up troubles, for example the relationship to the Pius Brotherhood or the irregularities with the Vatican, where the butler had let known indiscretions,” he said.

The reference to the Pius Brotherhood involved the ultra-right wing Catholic order founded by the French archbishop Marcel François Marie Joseph Lefebvre in virulent opposition to Vatican II, the ecumenical council convened in the early 1960s in an attempt by the Church hierarchy to make some adaptations to the political, social and cultural transformations of the post-World War II era.

Lefebvre and the Pius Brotherhood were identified with the most extreme forms of political reaction, defending the fascist regimes in Vichy France, Franco’s Spain and Salazar’s Portugal, as well as the military dictatorships of Jorge Videla in Argentina and Augusto Pinochet in Chile. In France, it backed the ultra-right wing nationalist Jean-Marie le Pen and strongly opposed immigration from Muslim countries.

Ratzinger, who had participated in and initially supported Vatican II, also became a determined opponent, particularly of those within the Church who cited its decisions to promote “liberation theology” in Latin America and elsewhere. He worked to reintegrate the Pius Brotherhood into the Church, lifting the ex-communication of four of its surviving bishops in 2009.

Then in the midst of this rapprochement, the Swiss head of the Pius Brotherhood, Bishop Bernard Fellay made a public speech describing Jews as the “enemies of the Church.”

Perhaps of more serious concern in the issues raised by Ratzinger’s brother is the so-called Vatileaks scandal involving internal Vatican documents, letters and diplomatic cables that were allegedly taken by the pope’s butler and leaked to Italian journalists.

These documents pointed to financial corruption in Vatican contracts and bitter divisions over measures being taken to comply with an investigation into money laundering by the Institute for Works of Religion, commonly known as the Vatican Bank.

Included in the documents was a letter warning of a plot to murder Ratzinger. Mentioned in the letter was Tarcisio Bertone, the Holy See’s secretary of state and the Vatican’s second most senior figure. Sections of the Italian media cast the letter as proof of a bitter power struggle between the Italian wing of the Church and the German and Polish wing, which has held the papacy for the past 35 years.

At his trial, the butler, Paolo Gabriele, claimed that he had leaked the documents to fight “evil and corruption.” Sentenced by an Italian court in October 2012 to 18 months in prison for theft, he was turned over to the Vatican and pardoned by the pope after two and a half months.

The scandals swirling around the Vatican bank and the Church’s finances recalled nothing so much as the exceedingly brief reign of John Paul I who died suddenly just 33 days after being selected as pope. The mysterious death has been linked to an investigation into the Vatican Bank’s relations with Banco Ambrosiano, in which it was the major shareholder. That bank, involved in illegal financial operations and linked to both the Mafia and the secret and fascistic P2 lodge, suffered a multi-billion-dollar collapse in 1982.

The other major crisis hanging over Ratzinger was the ever-growing wave of sexual abuse charges brought by people molested and raped by priests in both the US and Western Europe. The revelations of both rampant abuse of children and the systematic cover-up of these crimes by the Church hierarchy has contributed to the rising alienation of Catholics from the Church. At the same time, it has fueled the Vatican’s financial crisis, with hundreds of millions of dollars, particularly from the Church in the United States—one of the principal sources of Vatican funding—going to financial settlements with the victims.

Ratzinger not only presided over the Church’s handling of the sex abuse scandals while pope, but had been placed in charge of handling the issue by his predecessor Karol Wojtyla, “the Polish pope.” At the time, then-Cardinal Ratzinger was head of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, the successor institution to the Inquisition.

His ferocious pursuit in that capacity of “liberation theologists” and anyone within the Church questioning dogma on matters such as contraception, abortion, divorce, homosexuality, papal infallibility and celibacy for priests earned him the nicknames of “grand inquisitor” and, in German, the “Panzerkardinal.”

He was a bitter opponent not just of Marxism, but of all forms of philosophical materialism and the Enlightenment. He propagated backwardness and reaction, particularly in Europe, which he saw as the cultural heartland that was being lost to Catholicism. In the midst of the devastating economic crisis, he preached a renunciation of “materialism” and “sacrifice.”

In one of his last international tours, he visited both Mexico and Cuba, successfully lobbying their governments to dismantle barriers that were placed against the Catholic Church—historically the bulwark of oppression and reaction—by the revolutions in those countries. In Cuba, where the Vatican has functioned as a spearhead for the penetration of European and particularly Spanish capital, Ratzinger preached the efficacy of “market reforms.”

In the discussion of who will be Ratzinger’s successor, to be selected by the College of Cardinals made up largely of his appointees, it has been suggested that the next pope could be African.

Whether or not this happens, the suggestion itself is highly political and has an obvious precedent. In 1978, the Church tapped Wojtyla to serve as the first Polish pope at the outset of a deep-going crisis that was to lead to the dissolution of the Soviet Union and the Stalinist bureaucracies in Eastern Europe. Under Wojtyla’s papacy, the Church played an active role in this process. In particular, it worked to ensure that the powerful upsurge of Polish workers, which developed under the banner of the Solidarity movement, remained under the thumb of the Catholic Church and did not develop in an independent socialist direction.

The suggestion that an African could be picked as Ratzinger’s successor is intimately bound up with the turn by US and French imperialism and their NATO allies toward a new scramble for Africa aimed at using military force to impose neo-colonial control over the continent’s markets and resources at the expense of their rival, China.

Comments